In my Money Week column this week, I've been looking at how to get the British economy growing again. Here's a taster....

After the cuts, the growth story. Addressing the Confederation of British Industry in Birmingham at the start of the week the Prime Minister David Cameron tried to sound a more optimistic note on the economy. It wasn’t just going to be about slashing benefits, closing down theatres and arts centres, and making everyone work until they are ninety-five. The economy would soon be expanding again.

That is surely right. The U.K. can’t simply cut its way out of a budget deficit of 11% of GDP, the highest in out peace-time history. It needs to start growing again, and at a faster rate than it did in the last decade.

Unless tax revenues rise, and jobs are created to replace those lost in the public sector, the books are never going to be balanced again. Rising unemployment and collapsing firms will mean that tax revenues keep on going down. Very quickly you get into a vicious circle of cutting spending, leading to lower tax receipts, which means even more cuts. Only growth is the way to break out of that.

But how? In fact, there are plenty of good places to start. Cut corporation tax to encourage investment: reform welfare aggressively to increase the labour force: deregulate those industries that are still too protected: and create tax-free zones in those areas of the country where the state has crowded out the private sector.

There is no reason why the economy shouldn’t expand at the same time as the budget deficit is bought under control. Despite the simplistic Keynesianism that seems to have gripped much of the media, it is perfectly possible for economies to expand at the same time that the government is reducing its spending. There are two reasons for that. The government doesn’t create any money itself, it merely takes it from other people, either by taxing them, or by borrowing it from them. So its spending decreases demand as much as it increases it. Next, as government gets smaller, there are more resources for the private sector to exploit. As a general rule, the smaller the state is, the faster an economy can grow,

Indeed, the last time the UK embarked on significant spending cuts – under John Major’s government in the early to mid-1990s – the UK grew at an impressive rate, and plenty of new jobs were created. Two million jobs were created under the Major government of 1992-1997, which more than made up for the 700,000 jobs that were cut out of the public sector. Under Mrs Thatcher’s Tory government of the 1980s, the experience was similar: after the peak of the recession or the early 1980s, 2.97 million new jobs were created by 1990, which more than made up for the two million lost in manufacturing. There is no reason to suppose the UK can’t repeat that experience in the coming decade.

But it isn’t going to happen by magic.

You can expect to hear a lot of waffle from the government about boosting infrastructure spending, encouraging more lending to small business, promoting investment in green technologies, and cracking down on short-termism in the City. Most of it is nonsense. The Government has no idea which ‘green technologies’ will work in the future, and whether this country has any real competitive advantage in any of them. People have been fretting about the short-termism of the financial markets since Victorian times without ever finding a realistic way of doing anything about it. Nor does the government have any idea whether the banks should be lending more to small businesses, and if so, which ones.

In fact, the steps the government should take to get growth going again are far simpler. Here are four good places to start.

One, cut corporation tax. In Ireland, a 12.5% corporate tax rate made the country a magnet for investment from all around the world. It could do the same for the UK. Over the coming few years, dozens of ambitious new companies are going to be emerging out of the fast-growing economies of Brazil, China, India and Russia. Just as the Japanese did a generation ago, they will be looking for a base to expand into Europe. Britain should be the natural destination for them, as it was for the Japanese. But it won’t happen unless there is plenty of incentive for them to come here – and a low tax rates trumps just about everything else.

Two, reform welfare aggressively. The huge numbers of Polish immigrants who came to this country and found work in the last decade tells us the UK can easily create jobs for people that want them. There is no easier way of boosting growth than increasing the employment rate; GDP, remember, is just output per worker, multiplied by the numbers of workers. If you can move some of the roughly five million people now living in benefits into jobs, you not only save on their welfare cheques, you also boost the economy. That is what reforming welfare can achieve.

Three, deregulate protected parts of the economy. The Thatcher government of the 1980s freed up the economy to generate growth – mostly notably through privatisations.. This government should do the same. The most obvious candidate is land and building. It's virtually impossible to build anything, particularly in the South-East, which is one reason we have, for example, a relatively small tourist industry Make it easier to get permission for new buildings, and the jobs will follow.

Finally, create tax-free zones. Big parts of the UK - Wales, the North-East,

Northern Ireland - have reached Soviet levels of state dependency. The public

sector has crowded out any kind of private economy. Nothing can grow when the

state accounts for 60% or more of GDP. But just slashing state spending won't

work by itself. Instead, create virtually tax-free zones to encourage the

private sector to move into those areas as spending is cut.

Growth is not about picking winners, or choosing which sectors of the economy to promote. No one really has any idea, and least of all the government. But if it frees up space for entrepreneurs, the economy will respond – it has in the past, and it will do so again.

Monday, 1 November 2010

Thursday, 28 October 2010

An Interview with the Northern Echo.

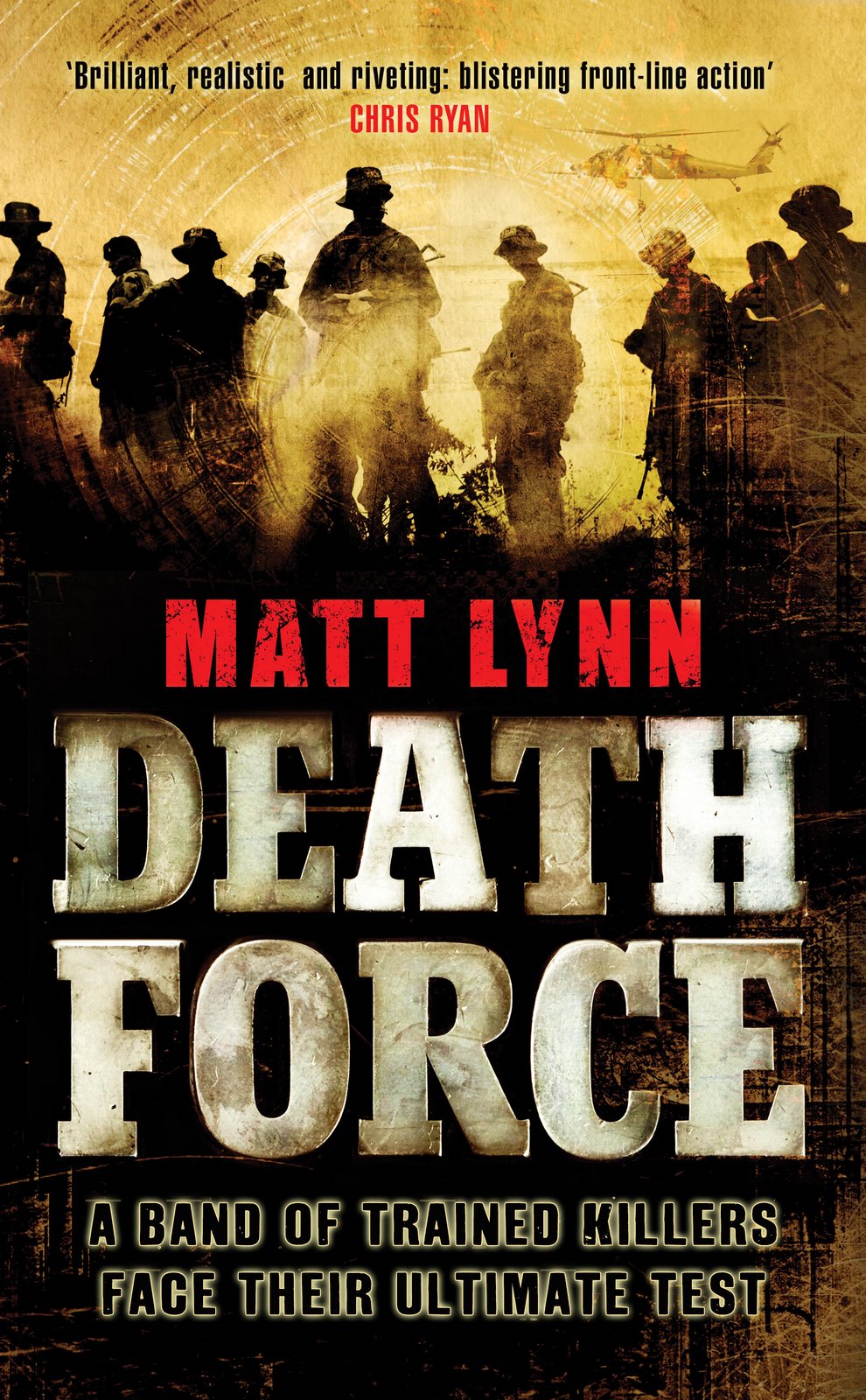

There's a great interview with me about the Death Force series in the Northern Echo. You can read it here.

Tuesday, 26 October 2010

Don't Diss Jane Austen....

Jane Austen has been getting some flak in the press, although I guess she can survive it. An academic has been studying her letters, noted how confused they are, and how different they are from her books, and concluded that her editor must have done a lot of re-writes on her books.

That story got lots of play in newspapers, and on the web. For some reason, people like the notion that authors don’t really write their own stuff, and there is some team of the people in the publishing house who actually put the book together

But anyway, whoever came up with this piece of research obviously knows very little about how writers actually work. There is a big difference between the writing we do for a living, which on the whole we take very seriously, edit and polish and worry about, and the writing we do like everyone else, which is dashed off without much thought.

Now obviously I don’t have much in common with Austen. I’m better at tank battles, for starters. Plus I’m still alive. But my e-mails, letters, Xmas cards, and indeed blog entries might well lead you to conclude that I couldn’t possibly have written my books either.

But, of course I did. And so, of course, did Jane Austen.

That story got lots of play in newspapers, and on the web. For some reason, people like the notion that authors don’t really write their own stuff, and there is some team of the people in the publishing house who actually put the book together

But anyway, whoever came up with this piece of research obviously knows very little about how writers actually work. There is a big difference between the writing we do for a living, which on the whole we take very seriously, edit and polish and worry about, and the writing we do like everyone else, which is dashed off without much thought.

Now obviously I don’t have much in common with Austen. I’m better at tank battles, for starters. Plus I’m still alive. But my e-mails, letters, Xmas cards, and indeed blog entries might well lead you to conclude that I couldn’t possibly have written my books either.

But, of course I did. And so, of course, did Jane Austen.

Tuesday, 12 October 2010

We Die Alone

One of the pleasures of writing for a living is that you come across all kinds of unexpected stuff. I’ve been getting stuck into the writing of ‘Ice Force’, the forth book in the Death Force series. As you might guess from the title, its set in the Arctic. To get my mind into the right place, I’ve been reading as much polar stuff as I get my hands on.

Most of it is exploration stories, and its useful for the atmosphere, and survival techniques. But not much has been written about Arctic warfare. Eventually, I stumbled across a book called ‘We Die Alone’, which was written in the early 1950s by David Howarth. It tells the story of Jan Baalstrud, a fairly ordinary Norwegian guy during the Second World War. He signs up with the British Army, and is sent on a commando mission into the far north of Norway. It goes terribly wrong from the start, the rest of his unit is killed, and he has to trek a massive distance chased by Nazis to escape.

The brilliance of the book is in its descriptions of Arctic warfare, and the endurance and fortitude of its hero. And it reminds you of what an extraordinary conflict WWII was, and how many ordinary people were caught up in extraordinary events.

The scene where Jan saws off his toes with a bread knife and a bottle of brandy to prevent them getting frostbite is memorable.

It’s now been reissued, with a forward by Andy McNab – and highly recommended.

Most of it is exploration stories, and its useful for the atmosphere, and survival techniques. But not much has been written about Arctic warfare. Eventually, I stumbled across a book called ‘We Die Alone’, which was written in the early 1950s by David Howarth. It tells the story of Jan Baalstrud, a fairly ordinary Norwegian guy during the Second World War. He signs up with the British Army, and is sent on a commando mission into the far north of Norway. It goes terribly wrong from the start, the rest of his unit is killed, and he has to trek a massive distance chased by Nazis to escape.

The brilliance of the book is in its descriptions of Arctic warfare, and the endurance and fortitude of its hero. And it reminds you of what an extraordinary conflict WWII was, and how many ordinary people were caught up in extraordinary events.

The scene where Jan saws off his toes with a bread knife and a bottle of brandy to prevent them getting frostbite is memorable.

It’s now been reissued, with a forward by Andy McNab – and highly recommended.

Monday, 11 October 2010

Why Ireland Should Follow Iceland

In my Money Week column this week, I've been looking at why Ireland should follow Iceland. Here's a taster...

A year ago, there was a joke in the City that went like this. “What’s the difference between Ireland and Iceland.? One letter and about six months.” But right now, you could turn that around, and make the punch line. “One letter, and a realistic economic policy.”

The Irish crisis goes from bad to worse. Despite making the deepest cuts to public spending imaginable, there is little sign of a durable economic recovery. Last week, the government raised the cost of the banking bail-out to 50 billion euros. Its deficit will amount to an eye-popping 32% of GDP this year.

In fact, the country should consider the Icelandic option instead. Go bust. Apologise to the rest of the world, but point out you can’t possibly pay all the debts your bankers ran up.

That is precisely what Iceland did. And despite the warnings of disaster, it is now looking in remarkably good shape. It is possible that the Irish, and indeed the rest of the world, have got it all wrong. You don’t have to bail out the bankers after all.

Two years ago, when the credit crunch hit, governments around the world bought into the idea that they had to rescue their banking system, no matter what the ultimate cost to the taxpayer. Lehman Brothers in the US was allowed to go under, but after that no significant bank was allowed to fail. In Britain, we rescued out Royal Bank of Scotland and Lloyds-HBOS. In France, BNP was helped out. Ireland was the most dramatic example. Its government was forced to bail out Anglo-Irish bank, Irish Nationwide, and others. On a worst-case scenario – and worst cases have a depressing way of coming true – the total bill for the rescues will come to 50 billion euros. The country has been close to bankrupted by the recklessness and irresponsibility of a small group of financiers. In other countries, the cost hasn’t been quite so horrendous, but taxpayers were still saddled with bills running into billions that will take a generation or more to pay off.

Only one country took an alternative route – Iceland. It is such a small place, and its bankers had run up such enormous liabilities, that it simply wasn’t feasible to keep all the Icelandic banks afloat. The country was bust.

The banks have successfully sold the argument that a country has to rescue its financial institutions when they run into trouble otherwise the whole nation will be ruined. The economy will collapse. The global markets will slam the door in your face. If the banks go down, so the argument goes, pretty soon we’ll all be living in caves again, scraping flints together to start a fire.

In fact, however, it turns out that a banking collapse isn’t so bad after all. In fact, Iceland is looking in remarkably good shape.

With some help from the IMF, the country is starting to recover. The economy will shrink by 1.9% this year but is forecast to grow by 3% in 2011. Interest rates are coming down again – the Icelandic central bank in September took interest rates down to 6.25%. Inflation is falling, and the Icelandic krona is rising again – it is up 17% against the euro this year. Capital controls, introduced during the emergency, are expected to start being lifted soon.

Despite all the warning of catastrophe, the country has survived and is putting itself back together again.

That isn’t to say it hasn’t suffered. Real incomes have fallen by about 20% since the financial collapse. Jobs have been lost on a huge scale, and savings wiped out. Ordinary people are angry enough about what happened to put the Prime Minister Geir Haarde, who presided overt the reckless expansion of the financial system, on trial for negligence.

But Iceland still functions. People still eat. The country has survived. By next year, it should start growing again. Modestly, no doubt, at first, but with a sharply devalued currency, and with credit starting to flow again, it should be able to pick itself up. It may be a surprisingly short time before it is allowed back into the global capital markets – after all, Russia defaulted on its debts amidst its financial crisis of 1998, but less than a decade later you could hardly move in Moscow for investment bankers looking for business. The financial markets don’t hold grudges. If you have money, they will do business with you.

So what lessons should we learn from the country’s experience?

Almost every government in the world has accepted the idea that they have to bail-out their banks if they run into trouble. But Iceland suggests it isn’t really true.

In fact, governments could simply protect domestic deposits. After that, they could just say they were very sorry, but there wasn’t enough money left to pay back all the debts the bankers had run up.

It would be better morally. Reckless, irresponsibly behaviour would not be rewarded. Bankers would have to think a lot harder about what risks they were taking, and what their consequences might be. And depositors would have to be a lot more careful about where they put their money, rather than just lazily assuming the government would pick up the tab for any losses.

And it would be better financially as well. Bad debts would get written off immediately, rather than remaining a millstone around the neck of the country for years to come.

Ireland is the most exposed country right now. The debts run up by its banks may well turn out to be quite literally unaffordable. But other countries should keep the Icelandic experience in mind next time a big bank gets into trouble.

It would be better just to let the banks collapse. So long as you protect domestic depositors, and keep the payment system working, it needn’t be the end of the world. Indeed, it may be well be quicker route to recovery the struggling for years to meet all the obligations run up by a handful of bankers.

A year ago, there was a joke in the City that went like this. “What’s the difference between Ireland and Iceland.? One letter and about six months.” But right now, you could turn that around, and make the punch line. “One letter, and a realistic economic policy.”

The Irish crisis goes from bad to worse. Despite making the deepest cuts to public spending imaginable, there is little sign of a durable economic recovery. Last week, the government raised the cost of the banking bail-out to 50 billion euros. Its deficit will amount to an eye-popping 32% of GDP this year.

In fact, the country should consider the Icelandic option instead. Go bust. Apologise to the rest of the world, but point out you can’t possibly pay all the debts your bankers ran up.

That is precisely what Iceland did. And despite the warnings of disaster, it is now looking in remarkably good shape. It is possible that the Irish, and indeed the rest of the world, have got it all wrong. You don’t have to bail out the bankers after all.

Two years ago, when the credit crunch hit, governments around the world bought into the idea that they had to rescue their banking system, no matter what the ultimate cost to the taxpayer. Lehman Brothers in the US was allowed to go under, but after that no significant bank was allowed to fail. In Britain, we rescued out Royal Bank of Scotland and Lloyds-HBOS. In France, BNP was helped out. Ireland was the most dramatic example. Its government was forced to bail out Anglo-Irish bank, Irish Nationwide, and others. On a worst-case scenario – and worst cases have a depressing way of coming true – the total bill for the rescues will come to 50 billion euros. The country has been close to bankrupted by the recklessness and irresponsibility of a small group of financiers. In other countries, the cost hasn’t been quite so horrendous, but taxpayers were still saddled with bills running into billions that will take a generation or more to pay off.

Only one country took an alternative route – Iceland. It is such a small place, and its bankers had run up such enormous liabilities, that it simply wasn’t feasible to keep all the Icelandic banks afloat. The country was bust.

The banks have successfully sold the argument that a country has to rescue its financial institutions when they run into trouble otherwise the whole nation will be ruined. The economy will collapse. The global markets will slam the door in your face. If the banks go down, so the argument goes, pretty soon we’ll all be living in caves again, scraping flints together to start a fire.

In fact, however, it turns out that a banking collapse isn’t so bad after all. In fact, Iceland is looking in remarkably good shape.

With some help from the IMF, the country is starting to recover. The economy will shrink by 1.9% this year but is forecast to grow by 3% in 2011. Interest rates are coming down again – the Icelandic central bank in September took interest rates down to 6.25%. Inflation is falling, and the Icelandic krona is rising again – it is up 17% against the euro this year. Capital controls, introduced during the emergency, are expected to start being lifted soon.

Despite all the warning of catastrophe, the country has survived and is putting itself back together again.

That isn’t to say it hasn’t suffered. Real incomes have fallen by about 20% since the financial collapse. Jobs have been lost on a huge scale, and savings wiped out. Ordinary people are angry enough about what happened to put the Prime Minister Geir Haarde, who presided overt the reckless expansion of the financial system, on trial for negligence.

But Iceland still functions. People still eat. The country has survived. By next year, it should start growing again. Modestly, no doubt, at first, but with a sharply devalued currency, and with credit starting to flow again, it should be able to pick itself up. It may be a surprisingly short time before it is allowed back into the global capital markets – after all, Russia defaulted on its debts amidst its financial crisis of 1998, but less than a decade later you could hardly move in Moscow for investment bankers looking for business. The financial markets don’t hold grudges. If you have money, they will do business with you.

So what lessons should we learn from the country’s experience?

Almost every government in the world has accepted the idea that they have to bail-out their banks if they run into trouble. But Iceland suggests it isn’t really true.

In fact, governments could simply protect domestic deposits. After that, they could just say they were very sorry, but there wasn’t enough money left to pay back all the debts the bankers had run up.

It would be better morally. Reckless, irresponsibly behaviour would not be rewarded. Bankers would have to think a lot harder about what risks they were taking, and what their consequences might be. And depositors would have to be a lot more careful about where they put their money, rather than just lazily assuming the government would pick up the tab for any losses.

And it would be better financially as well. Bad debts would get written off immediately, rather than remaining a millstone around the neck of the country for years to come.

Ireland is the most exposed country right now. The debts run up by its banks may well turn out to be quite literally unaffordable. But other countries should keep the Icelandic experience in mind next time a big bank gets into trouble.

It would be better just to let the banks collapse. So long as you protect domestic depositors, and keep the payment system working, it needn’t be the end of the world. Indeed, it may be well be quicker route to recovery the struggling for years to meet all the obligations run up by a handful of bankers.

Thursday, 7 October 2010

Fire Force Audio Book

I received the audip book of Fire Force today. It sounds great. You can buy it here.

Tuesday, 5 October 2010

Judging A Book By Its Cover,,,

One of the questions writers get asked is how much they say they have over their covers. To which the simple answer is: About as much say as we do over the weather.

My experience is that publishers send you the cover, and then whilst theoretically you could throw a tantrum and say you didn’t like it, that probably wouldn’t be a very welcome response.

Fortunately, I’ve never been in a position where I haven’t like a cover. I’ve just received the jacket for ‘Shadow Force’ and I think it’s fantastic: exciting, direct, in keeping with the previous two books in the series, but different enough to mark out its own space. (Then again, when a book is about mercenaries and pirates, it’s quite hard not to come up with a decent jacket).

And, of course, authors shouldn’t assume they know what is the best cover for their book. The editor and the illustrator will have their own take on it, and how it fits into the market, who it is going to appeal to, and how it will stand out from the rest of the books on the market.

That said, it would be awful to see a cover you really didn’t like on your book. After all, it is the most obvious statement about your work.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)